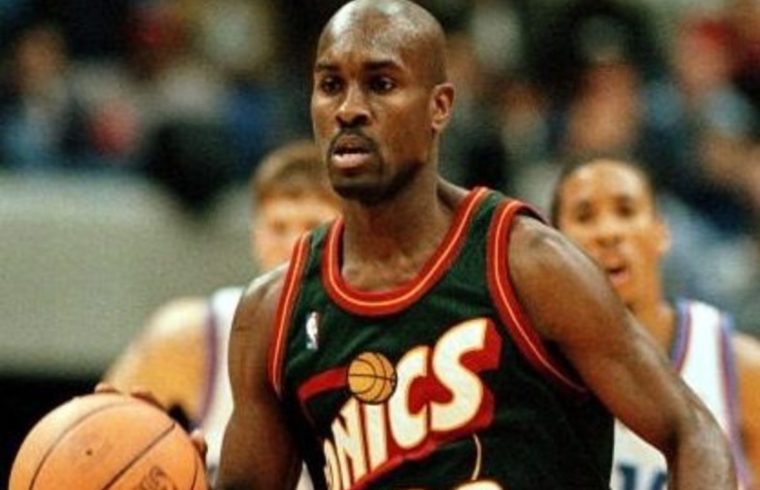

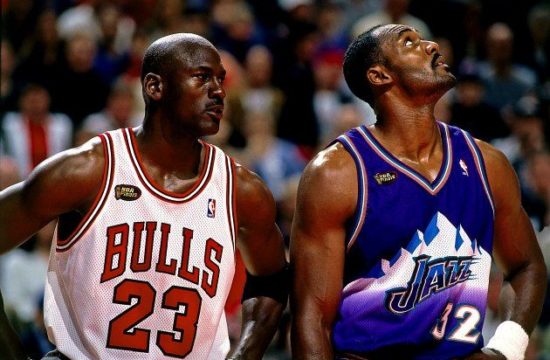

Do a Google image search for Gary Payton, and one of the earliest and most frequent pictures you’ll see is of him jawing at Michael Jordan in the middle of the 1996 NBA Finals. It looks like Payton is about to drop an F-bomb … and according to his recollections, that’s probably a safe bet.

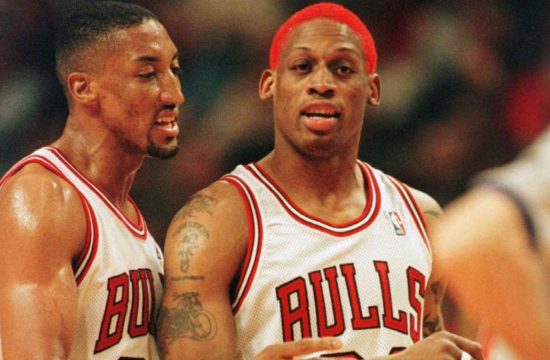

“It was a lot everything,” Payton said. “A lot of ‘s—‘, ‘f—‘, ‘f— you’. And then Ron Harper got into it, Scottie Pippen got into it, Phil [Jackson] got into it. We were going back and forth with the ‘f— you.'”

Sometimes the Google algorithms create an unfair or unfortunate link, capturing a moment that doesn’t truly represent a person’s life. This isn’t one of those times. If the Basketball Hall of Fame had busts of its enshrinees like its pro football counterpart, Payton’s would have to be cast with his head cocked and mouth open, perpetually talking trash.

This isn’t just who he is, it’s what made him who he is: one of the game’s elite players, worthy of induction among the all-time greats during this weekend’s ceremonies in Springfield, Mass. It comes from a combination of the Oakland playgrounds and his father, Al Payton, also known as “Mr. Mean.”

“He installed that toughness in me, and that swagger,” Payton said. “Having to play against all the guys in Oakland, they’re trying to beat you up. You knew you had to do it or you’d be punked all the time. Every day, I walked with a chip on my shoulder … and after the game, we’ll see what happens.”

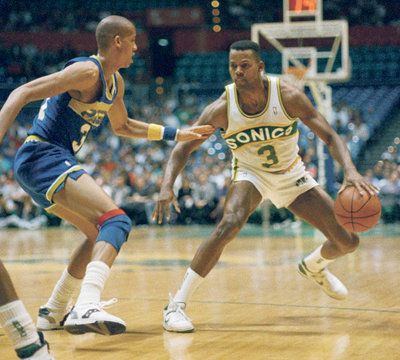

The other element that defined Payton — the lockdown defense that inspired the nickname “The Glove” — he attributes to Ralph Miller, his coach at Oregon State. In college Payton did defensive slide after defensive slide, was taught to put his quick hands to good use and learned that there’s more to the game than scoring.

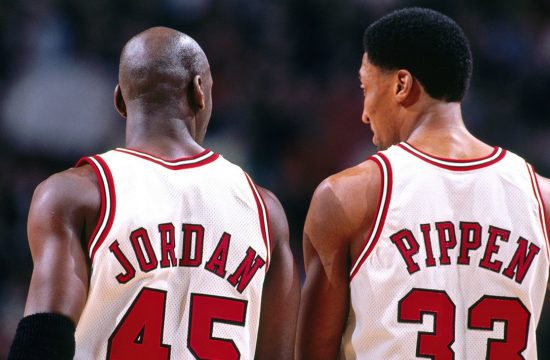

Defense is a big part of the story behind that picture. After the Seattle SuperSonics fell behind the Chicago Bulls 3-0 in the series, Seattle coach George Karl gave Payton the primary defensive assignment on Jordan. What followed was a small bit of NBA history: Payton held Jordan to 37 percent shooting and 23, 26 and 22 points over the next three games. It was the only time Jordan scored fewer than 30 points in three consecutive NBA Finals games. And certainly the only time an opponent D’d him up so defiantly.

It didn’t matter that Payton was dealing with a calf injury that had him in an oxygen chamber after home games. No matter that Payton’s offense was too valuable for him to get in foul trouble. He took on the assignment with zeal.

“

You can’t back down on [Jordan]. If you do, he’s like a wolf, he’s going to eat everything. He knew I wasn’t going to back down. I had to realize or see if he is really about being a dog, about this neighborhood stuff. I went at him. It was just me being me.”

“— Gary Payton

“You’ve got to get back at Jordan,” Payton said. ” You can’t back down on him. If you do, he’s like a wolf, he’s going to eat everything. He knew I wasn’t going to back down. I had to realize or see if he is really about being a dog, about this neighborhood stuff. I went at him. It was just me being me.”

That “me” was unlike anyone else — then or now. At a wiry 6-foot-4, 180 pounds, Payton overpowered with willpower more than physical force. He could defend any guard from Jordan on down and was skilled enough offensively to rank among the NBA’s top 30 all-time scorers and top 10 in assists. Payton wasn’t a unique physical specimen like Shaquille O’Neal; he was unique because of his all-inclusive skill set in one audacious package. You can find traces of Jordan in Kobe Bryant. You won’t find a duplicate of Payton anywhere.

“There’s only one person out there who can do it — and I think he can do it, but I don’t know if his mentality is there — and that’s [Rajon] Rondo,” Payton said. “He can’t score like I did on the offensive end. He can do it on the defensive end. … I wish he would score a little better.”

Even worse than the lack of Payton descendants in the game today is the fact that there’s no place to retire his jersey. The SuperSonics moved to Oklahoma City, became the Thunder and effectively became dead in Payton’s eyes.

“I blame the people that had the ownership that let it go,” he said, referring to the group led by Howard Schultz, who sold to investors from Oklahoma. “I think they know that [move] was going to happen. They should be ashamed of themselves. I don’t blame it on anybody else but that organization that had it at the time. The fans got the raw deal.”

Not only are the Seattle fans missing out on the upcoming prime years of Kevin Durant‘s and Russell Westbrook’s careers, they’re missing out on the chance to honor the many great games Payton played in that No. 20 Sonics jersey.